Understanding credit risk ratings is crucial for navigating the complexities of finance. These ratings, assigned by agencies like Moody’s, S&P, and Fitch, provide a snapshot of a borrower’s creditworthiness, influencing everything from loan interest rates to investment decisions. This exploration delves into the intricacies of these ratings, examining the factors that determine them, their implications for investors and borrowers, and their role in a dynamic economic landscape.

From the historical context of credit rating agencies to the current methodologies used to assess risk, we will uncover how these ratings are determined and the significant impact they have on the global financial system. We will also examine how macroeconomic factors influence credit ratings and explore the relationship between credit scores and credit risk assessment for everyday consumers.

Introduction to Credit Risk Ratings

Credit risk ratings are crucial tools in the financial world, providing a standardized assessment of the likelihood that a borrower will default on its debt obligations. These ratings help investors, lenders, and other stakeholders make informed decisions about the level of risk associated with lending money or investing in a particular entity. Understanding these ratings is essential for navigating the complexities of the financial markets.

The Purpose of Credit Risk Ratings

Credit ratings aim to simplify the complex process of evaluating creditworthiness. They translate extensive financial data and analysis into a concise, easily understood rating, allowing investors to quickly compare the relative risk of different investments. This facilitates efficient capital allocation, as investors can readily identify opportunities that align with their risk tolerance. Ratings also influence borrowing costs; entities with higher credit ratings typically secure loans at lower interest rates, reflecting the lower perceived risk.

A Brief History of Credit Rating Agencies

The modern credit rating industry emerged in the late 19th century, with early efforts focusing primarily on railroad bonds. However, the industry truly took off after the Great Depression, as investors sought ways to assess the risk of investments in a more systematic manner. The rise of large-scale corporate finance and the growth of the bond market fueled the expansion of credit rating agencies.

Today, a handful of global agencies dominate the landscape, wielding significant influence over the financial markets.

Examples of Different Credit Rating Scales Used Globally

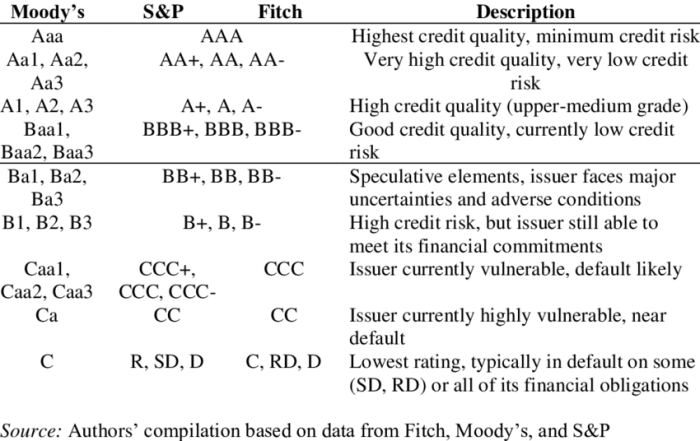

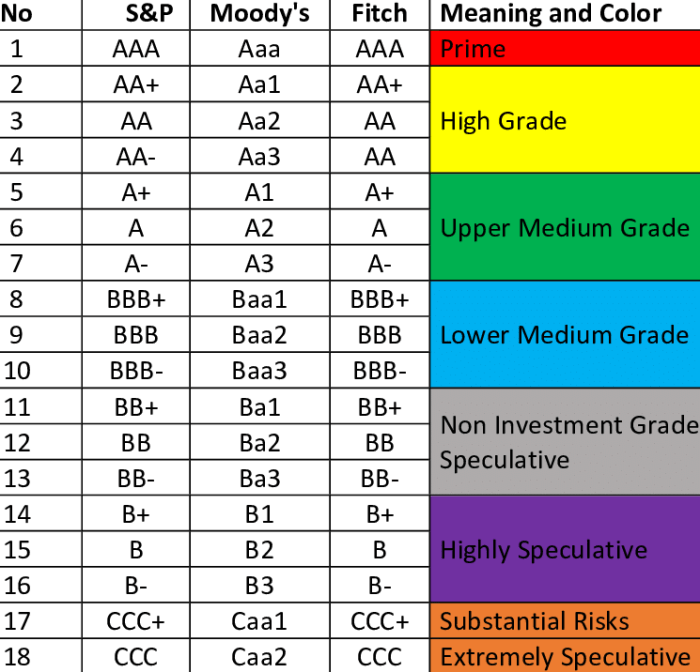

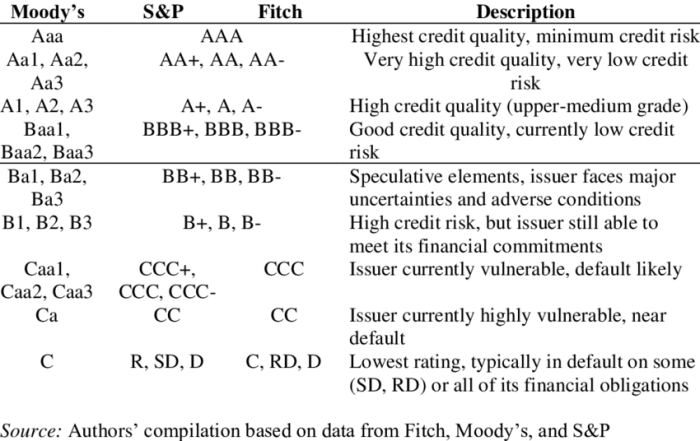

Several credit rating scales exist, each with its own nuances, but they generally share a common structure. Ratings typically range from AAA (or equivalent) representing the highest creditworthiness, down to D (or equivalent) indicating default. Here are some examples:

- Standard & Poor’s (S&P): AAA, AA, A, BBB, BB, B, CCC, CC, C, D

- Moody’s Investors Service: Aaa, Aa, A, Baa, Ba, B, Caa, Ca, C, D

- Fitch Ratings: AAA, AA, A, BBB, BB, B, CCC, CC, C, D

While the letters and specific notations may vary slightly, the underlying principle of assigning ratings based on risk remains consistent across agencies. The higher the rating, the lower the perceived risk of default.

Comparison of Major Credit Rating Agencies and Their Methodologies

Although all major credit rating agencies aim to assess credit risk, their specific methodologies and approaches can differ. This table offers a simplified comparison:

| Agency | Methodology Focus | Rating Scale | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard & Poor’s (S&P) | Quantitative and qualitative analysis, focusing on financial strength and business risk | AAA to D | Financial ratios, industry analysis, management quality |

| Moody’s Investors Service | Comprehensive assessment encompassing financial, economic, and industry factors | Aaa to D | Debt levels, cash flow, regulatory environment |

| Fitch Ratings | Balanced approach combining quantitative and qualitative analysis | AAA to D | Liquidity, profitability, governance structure |

Factors Determining Credit Risk Ratings

Credit risk ratings, crucial for assessing the likelihood of a borrower defaulting on their debt obligations, are determined by a complex interplay of financial and qualitative factors. Rating agencies meticulously analyze these elements to arrive at a comprehensive assessment of creditworthiness. This analysis goes beyond simply looking at numbers; it involves a deep dive into the borrower’s financial health, operational efficiency, and overall business environment.

Key Financial Ratios in Credit Risk Assessment

Several key financial ratios provide a quantitative snapshot of a borrower’s financial health and are instrumental in credit risk assessment. These ratios offer insights into profitability, liquidity, leverage, and solvency, allowing for a comparative analysis across different borrowers and industries. Analyzing trends in these ratios over time is equally important as it reveals the direction of the borrower’s financial performance.

- Debt-to-Equity Ratio: This ratio (Total Debt / Total Equity) indicates the proportion of a company’s financing that comes from debt versus equity. A high ratio suggests higher financial risk as the company relies heavily on debt financing.

- Interest Coverage Ratio: This ratio (Earnings Before Interest and Taxes (EBIT) / Interest Expense) measures a company’s ability to meet its interest obligations. A lower ratio signifies a greater risk of default.

- Current Ratio: This ratio (Current Assets / Current Liabilities) indicates a company’s ability to meet its short-term obligations. A ratio below 1 suggests potential liquidity problems.

- Quick Ratio: Similar to the current ratio, but more conservative, this ratio ( (Current Assets – Inventory) / Current Liabilities) excludes inventory, which may not be easily liquidatable.

- Return on Assets (ROA) and Return on Equity (ROE): These ratios (Net Income / Total Assets and Net Income / Total Equity respectively) reflect the profitability and efficiency of a company’s asset utilization and shareholder investment.

Qualitative Factors in Credit Rating Analysis

Beyond the quantitative measures, qualitative factors play a crucial role in credit rating analysis. These factors often provide a context for understanding the financial ratios and offer insights into the long-term sustainability of the borrower’s business model. Ignoring these qualitative aspects can lead to inaccurate credit risk assessments.

- Management Quality: The experience, competence, and integrity of a company’s management team significantly influence its ability to navigate challenges and achieve its financial goals. A strong management team can mitigate risks and improve the company’s prospects.

- Industry Trends: The overall health and outlook of the industry in which the borrower operates are critical considerations. A declining industry with increasing competition can negatively impact a company’s financial performance, regardless of its internal strengths.

- Regulatory Environment: Changes in regulations or government policies can significantly affect a company’s operations and financial stability. Companies operating in highly regulated industries face unique risks.

- Corporate Governance: Strong corporate governance structures, including transparent accounting practices and effective internal controls, reduce the likelihood of financial irregularities and improve creditworthiness.

Short-Term versus Long-Term Debt in Credit Risk Evaluation

The evaluation of short-term and long-term debt differs significantly in credit risk assessment. Short-term debt, while easier to manage in the short run, requires continuous refinancing and poses a higher risk of liquidity problems if not managed effectively. Long-term debt, while providing financial stability, can become burdensome if the company’s financial performance deteriorates over time. The maturity profile of a company’s debt is therefore a crucial aspect of credit risk analysis.

A company with a large proportion of short-term debt maturing soon may face refinancing difficulties, especially during economic downturns, even if its long-term prospects are strong. Conversely, a company with substantial long-term debt might face difficulties if its cash flows are insufficient to service its debt obligations over the long term.

Common Red Flags Indicating High Credit Risk

Identifying red flags is crucial for mitigating potential losses. These warning signs, when present, indicate a higher probability of default.

- Consistent decline in profitability and revenue.

- High debt levels and low interest coverage ratios.

- Deteriorating liquidity, reflected in falling current and quick ratios.

- Frequent late payments to suppliers or creditors.

- Significant accounting irregularities or questionable accounting practices.

- Negative cash flow from operations.

- Management turnover or significant internal conflicts.

- Exposure to significant industry-specific risks.

Interpreting Credit Risk Ratings

Credit risk ratings, issued by agencies like Moody’s, S&P, and Fitch, provide a concise assessment of a borrower’s creditworthiness. Understanding these ratings is crucial for investors, lenders, and borrowers alike. Different rating categories represent varying levels of risk, influencing investment decisions and borrowing costs. This section will explore the meaning of these categories, the implications of rating changes, and the inherent limitations of these assessments.

Meaning of Different Rating Categories

Credit rating agencies employ alphabetical grading systems, typically ranging from AAA (highest quality) to D (default). AAA signifies the lowest expectation of default, indicating extremely strong capacity to meet financial obligations. Ratings like AA and A represent high-quality obligations with a low expectation of default, though slightly higher than AAA. Ratings in the BBB category indicate adequate credit quality, suggesting some degree of susceptibility to adverse economic conditions.

Below BBB, ratings such as BB, B, CCC, CC, and C reflect progressively higher credit risk, with a substantial probability of default. Finally, a D rating signifies default, indicating that the borrower has failed to meet its financial obligations. The specific nuances within each category (e.g., A1, A2, A3) further refine the risk assessment, providing a more granular view of creditworthiness.

Implications of Credit Downgrades

A credit downgrade carries significant implications for both borrowers and lenders. For borrowers, a downgrade typically translates to increased borrowing costs. Lenders will demand higher interest rates to compensate for the increased perceived risk of default. This can severely impact a company’s financial flexibility and profitability, potentially leading to difficulty in securing further financing. For lenders, a downgrade signals increased risk of losses.

They may need to set aside more capital to cover potential defaults, reducing their profitability. In extreme cases, a downgrade can trigger margin calls, requiring lenders to provide additional collateral or face liquidation of their holdings. For example, a significant downgrade for a large corporation could lead to a sell-off of its bonds, impacting its stock price and overall market valuation.

Limitations of Credit Risk Ratings

While credit ratings provide valuable insights, it’s crucial to acknowledge their limitations. Ratings are not a guarantee of future performance; they are merely an assessment of risk based on historical data and projections. Furthermore, the rating agencies’ methodologies and models can be complex and opaque, making it difficult for users to fully understand the rationale behind a specific rating.

The ratings can also be subject to bias, either explicitly or implicitly, influenced by factors such as regulatory pressures or conflicts of interest. Finally, ratings can lag behind actual changes in creditworthiness, meaning a company’s financial health might deteriorate significantly before a downgrade is reflected in its rating. Therefore, it’s essential to use credit ratings as one factor among many when assessing credit risk, rather than relying on them solely.

Investor Response to Different Credit Rating Levels

The following table illustrates the typical investor response to different credit rating levels. It is important to note that these are generalizations, and actual investor behavior can vary based on market conditions and individual investor preferences.

| Rating Category | Typical Investor Response | Yield/Return Expectation | Investment Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| AAA | High demand, low risk perception | Low yield | Safe haven investment, core holdings |

| BBB | Moderate demand, acceptable risk | Moderate yield | Diversification, moderate risk tolerance |

| BB | Lower demand, higher risk perception | Higher yield | Speculative investment, higher risk tolerance |

| CCC | Very low demand, high risk of default | Very high yield (or potential for loss) | High-risk, high-reward strategy, only for experienced investors |

Credit Risk Ratings and Investment Decisions

Credit ratings play a crucial role in shaping investment decisions across the spectrum of investors, from individual retail investors to large institutional players. Understanding how ratings influence investment strategies, portfolio construction, and ultimately, market pricing is essential for navigating the complexities of the financial markets.

Credit Ratings and Investor Decision-Making

Credit ratings provide a standardized, readily understandable assessment of an issuer’s creditworthiness. Institutional investors, such as pension funds and mutual funds, heavily rely on these ratings to manage risk within their portfolios. They often have internal guidelines that restrict investment in securities below a certain rating threshold. Retail investors, while perhaps less sophisticated in their analysis, also use ratings as a quick reference point when evaluating investment opportunities, seeking out higher-rated, less risky options.

For example, a retail investor might prioritize purchasing bonds rated AAA or AA over those with lower ratings, reflecting a preference for lower risk. Institutional investors might use credit ratings to build diversified portfolios, combining higher-rated, lower-yield bonds with lower-rated, higher-yield bonds to achieve a desired risk-return profile.

Credit Ratings and Portfolio Diversification

Credit ratings are integral to effective portfolio diversification strategies. By incorporating a range of credit ratings, investors can mitigate risk. A portfolio solely composed of high-rated bonds may offer lower returns, while one exclusively invested in lower-rated bonds may expose the investor to significantly higher default risk. A balanced portfolio, carefully constructed with diverse credit ratings, aims to optimize the risk-return trade-off.

For example, a pension fund might allocate a portion of its assets to high-grade bonds for stability, another portion to medium-grade bonds for higher yield, and a smaller allocation to high-yield bonds to enhance returns while accepting a higher level of risk. This diversified approach aims to minimize losses in the event of a default by one issuer.

Credit Ratings and Bond Yields

The relationship between credit ratings and bond yields is inverse. Bonds with higher credit ratings, indicating lower default risk, generally offer lower yields. Conversely, bonds with lower credit ratings, reflecting higher default risk, tend to offer higher yields to compensate investors for the increased risk. This reflects the market’s pricing of risk; investors demand a premium for accepting higher default risk.

For example, a newly issued AAA-rated corporate bond might offer a yield of 3%, while a similarly structured BB-rated bond from a different company might offer a yield of 8% to reflect the increased risk of potential default.

Impact of Credit Rating Changes on Capital Raising

A change in credit rating can significantly impact a company’s ability to raise capital. A downgrade, signaling increased default risk, typically leads to higher borrowing costs. Conversely, an upgrade, indicating improved creditworthiness, can reduce borrowing costs. For example, imagine a hypothetical company, “XYZ Corp,” with a BBB rating that needs to issue new bonds to finance expansion.

If a credit rating agency downgrades XYZ Corp to BB, the company will likely face higher interest rates on its new bonds, making the financing more expensive and potentially hindering its expansion plans. This increased cost of capital could even force the company to reconsider or scale back its expansion plans. Conversely, an upgrade from BB to BBB would likely result in lower borrowing costs, making the financing more attractive and easier to secure.

Credit Card Credit Risk, Credit Score Relationship

Credit scores are a cornerstone of credit risk assessment, particularly for credit cards. Lenders utilize these scores to predict the likelihood of a borrower defaulting on their payments. A higher credit score generally indicates a lower risk, leading to more favorable interest rates and credit limits. Conversely, a lower score suggests a higher risk, potentially resulting in higher interest rates, lower credit limits, or even rejection of the application.

This relationship is crucial for both consumers and financial institutions.Credit card usage significantly impacts a credit score through several key factors. Responsible credit card management, such as paying bills on time and maintaining low credit utilization, positively influences the score. Conversely, missed payments, high balances, and frequent applications for new credit can negatively impact it. Understanding this dynamic empowers consumers to manage their credit effectively.

Credit Card Usage and Credit Score Impact

The impact of credit card usage on a credit score is multifaceted. Payment history, the most significant factor, directly reflects a borrower’s reliability. Consistent on-time payments contribute positively, while late or missed payments severely damage the score. Credit utilization, representing the proportion of available credit used, is another crucial factor. Keeping utilization low (ideally below 30%) demonstrates responsible credit management and improves the score.

Conversely, consistently high utilization suggests financial strain and increases perceived risk. The number of credit inquiries and the age of credit accounts also play roles; numerous inquiries suggest excessive borrowing, while a longer credit history indicates greater financial stability.

Credit Risk Assessment Methods: Credit Cards vs. Other Loans

While credit scores are central to credit risk assessment for both credit cards and other loans, the specific methods and emphasis can differ. Credit card applications often involve a more streamlined process, relying heavily on credit scores and automated systems. For larger loans like mortgages or auto loans, lenders typically conduct more in-depth reviews, considering factors beyond credit scores, such as income verification, debt-to-income ratios, and asset evaluation.

This difference reflects the varying levels of risk and financial commitment involved. For instance, a mortgage lender will consider a wider range of factors to assess long-term financial stability.

Strategies for Improving Credit Score and Reducing Credit Risk

Improving a credit score and reducing credit risk involves proactive financial management. The following strategies are effective in achieving this goal:

The importance of these strategies lies in their cumulative effect on building a strong credit profile. Consistent application of these practices will positively impact credit scores and reduce the perceived risk associated with credit card applications and other forms of borrowing.

- Pay all bills on time, every time.

- Keep credit utilization low (below 30% is ideal).

- Limit applications for new credit to avoid excessive inquiries.

- Monitor credit reports regularly for errors and inaccuracies.

- Consider a secured credit card to build credit history if needed.

- Maintain a diverse mix of credit accounts (e.g., credit cards and installment loans).

Impact of Economic Conditions on Credit Risk Ratings

Credit risk ratings are not static; they are dynamic indicators that reflect the ever-changing economic landscape. Macroeconomic factors exert a significant influence on a borrower’s ability to meet its debt obligations, directly impacting creditworthiness and, consequently, its credit rating. Understanding this interplay is crucial for investors, lenders, and businesses alike.Macroeconomic factors such as interest rates, inflation, and the overall state of the economy (e.g., recession or expansion) significantly influence credit risk ratings.

These factors affect a borrower’s profitability, cash flow, and ultimately, their creditworthiness. Periods of economic uncertainty often lead to adjustments in credit rating methodologies to account for the heightened risk.

Interest Rate Changes and Their Impact on Credit Ratings

Changes in interest rates have a profound effect on borrowers, particularly those with variable-rate debt. A sudden increase in interest rates can dramatically increase borrowing costs, reducing profitability and potentially leading to defaults. Companies with high levels of debt are particularly vulnerable. For instance, a company heavily reliant on short-term debt financing might see its credit rating downgraded if interest rates rise sharply, as its interest expense increases, squeezing its cash flow.

Conversely, a decrease in interest rates can improve a borrower’s financial position, potentially leading to an upgrade in their credit rating. This is because lower interest rates reduce borrowing costs, freeing up cash flow for other purposes.

Inflation’s Influence on Credit Risk Assessments

High inflation erodes purchasing power and can increase input costs for businesses. This can lead to reduced profitability and increased financial strain, ultimately impacting a borrower’s ability to repay debt. Companies with inelastic demand (where demand is less sensitive to price changes) might be less affected, while those with elastic demand (where demand is highly sensitive to price changes) could experience significant revenue declines.

Credit rating agencies closely monitor inflation rates and their impact on various sectors to adjust their assessments accordingly. For example, a prolonged period of high inflation might lead to downgrades for companies in sectors particularly vulnerable to price increases.

Economic Downturns and Default Rates

Economic downturns, such as recessions, are typically associated with increased default rates among borrowers. During these periods, businesses experience reduced sales, higher unemployment, and tighter credit conditions. This makes it harder for businesses to service their debt, leading to a higher probability of default. The severity of the impact varies depending on the industry and the borrower’s financial health.

For example, cyclical industries (those highly sensitive to economic fluctuations) are often more susceptible to defaults during recessions compared to counter-cyclical industries (those that perform well during recessions).

Credit Rating Agency Methodological Adjustments During Economic Uncertainty

During periods of economic uncertainty, credit rating agencies often adjust their methodologies to account for the heightened risk. This might involve: increasing the weight given to certain financial ratios (such as debt-to-equity ratio or interest coverage ratio), incorporating macroeconomic forecasts into their models, and adjusting their default probabilities. They might also increase the scrutiny of borrowers’ financial statements and stress test their financial projections under various adverse economic scenarios.

The goal is to provide a more accurate and timely assessment of credit risk during turbulent times.

Scenario: A Sudden Increase in Interest Rates

Imagine a sudden and significant increase in interest rates, say, a 2% increase in the benchmark interest rate. This event would have a cascading effect across various sectors. Real estate companies, highly leveraged with variable-rate mortgages, would face increased financing costs, potentially leading to downgrades. Similarly, companies with significant short-term debt would experience a sharp increase in interest expenses, squeezing their profit margins and potentially leading to credit rating downgrades.

In contrast, companies with low debt levels and strong cash flow might be less affected, potentially maintaining their credit ratings or even experiencing upgrades if they can capitalize on the situation by acquiring distressed assets. The impact on the consumer sector would also be felt, with increased interest rates on credit cards and loans impacting household debt and potentially leading to increased consumer defaults.

In conclusion, credit risk ratings serve as vital signposts in the financial world, guiding investment decisions, shaping borrowing costs, and reflecting the overall health of borrowers and the economy. While not without limitations, understanding these ratings and the factors driving them empowers individuals and institutions to make more informed financial choices, mitigating risk and maximizing opportunities within the complex landscape of credit and investment.

Answers to Common Questions

What is the difference between a credit rating and a credit score?

A credit rating assesses the creditworthiness of corporations and governments, while a credit score assesses the creditworthiness of individuals.

How often are credit ratings updated?

Credit ratings are typically reviewed periodically, but the frequency varies depending on the agency and the specific circumstances of the borrower.

Can a credit rating be withdrawn?

Yes, a credit rating agency may withdraw a rating if it no longer has sufficient information to support its assessment or if the borrower requests it.

What happens if a company’s credit rating is downgraded?

A downgrade typically leads to higher borrowing costs, reduced investor confidence, and potentially difficulty in raising capital.